By Sarah Peiper

Dr. Stephen Dantzig earned his Doctor of Psychology degree from Rutgers University, focusing his dissertation on the cognitive development of children with cerebral palsy and spina bifida.

Diagnosed with cerebral palsy in childhood, he dedicated his career to working with individuals with disabilities, beginning as a volunteer with children with severe autism. He served as a school psychologist for nearly four decades in New York, New Jersey, California and Hawai’i. He was also a graduate school professor and author of 14 books, over 100 articles on photography and two publications on cognitive assessment. In 2012, he wrote an autobiography, Get Up, Your Bus Is Here: Living MY Life with Cerebral Palsy, in which he shares his experiences, including memorable stories, like losing a cane at the Hunter Mountain Ski Resort in New York and another 30 years later in the surf at Sandy Beach in Hawai’i. (The book is out of print, but you can read it for free here.)

Dr. Dantzig now serves as the education and outreach program manager at United Cerebral Palsy (UCP) Association of Hawai’i and serves on its board of directors. UCP National sat down with Dr. Dantzig to learn more about his journey and what he hopes to accomplish in his role at UCP Association of Hawai’i.

Q: Can you share some of your early experiences living with cerebral palsy?

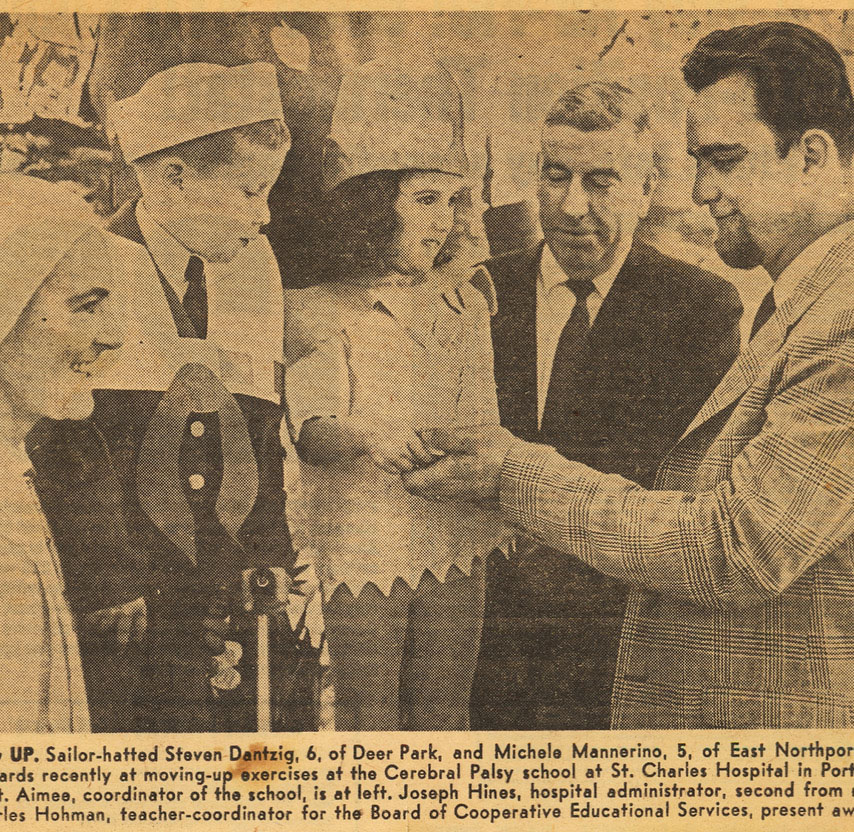

Dr. Dantzig: My parents knew early on that something wasn’t quite right. The doctors said it was just a delay. St. Charles Hospital and Rehabilitation in Port Jefferson, New York, was (and still is) affiliated with UCP. I recall they had a clinic for people with disabilities once per month. We went to the clinic, and my mom said they took one look and said, “He has cerebral palsy.” Mom cried, not because of the diagnosis, but because someone finally validated her concerns. It was a huge turning point because it changed my parents’ response from confusion to understanding, which impacted me — it changed their response to me.

After that initial diagnosis, a psychologist did an assessment and determined that my cerebral palsy was physical, not cognitive. The doctor told my parents, “He is going to college. Make him as independent as he can. Make him do whatever he can himself. Let him go.” And they did.

Part of the systemic problem surrounding disabilities is that sometimes, they would rather not diagnose an intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) until they are older. My opinion is that the sooner you can tell parents the reality, the sooner they can begin to deal with it. If we don’t acknowledge them up front, then I think we’re not really providing the kind of services we should be. It’s one reason why early diagnosis and intervention is so critical.

Q: How has your perspective on disability evolved over the years?

Dr. Dantzig: My parents raised me to do things myself, whatever that looked like. I was raised to be independent; that is where I developed the thought that I didn’t need help — I could manage on my own. Which was true! I could do quite a lot. I wasn’t particularly graceful about it, but I could get it done.

And so, for a very long time, I would refuse help. “No, I can do it myself!” I would drag my book bag through Penn Station. People would offer help, and I would say, “No, thank you.” For years!

One day, about 15 years later, I was running late for the train. I finally asked for help. And, of course, someone helped me make it to the train without a second thought. That was an ah-ha moment. I realized that it is OK to ask for help. Independence doesn’t mean isolation. The human experience is about connection. There is kindness, gratitude, respect and love that you miss out on when you go it entirely alone.

So now, my perspective on disability is two-pronged. People want to help, and I see the value in sharing that experience and allowing people to be helpful, which fosters that wonderful circle of gratitude — thank and be thanked. But like the doctors and my parents thought while I was growing up, there are times when help hinders. For example, people may not understand that physically pulling on me to “help” me up when my muscles are trying to do something else is quite painful. Sometimes, people need to respect a no thank you, but we all must assume the intention is good.

Q: What were some of the biggest challenges you faced growing up with cerebral palsy, and how did you overcome them?

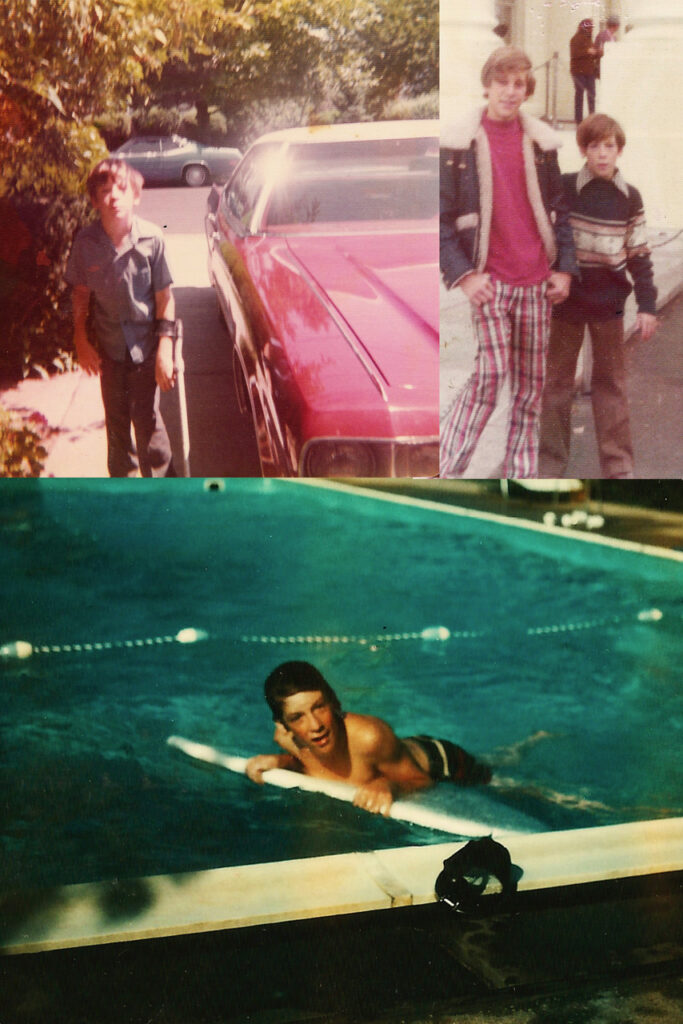

Dr. Dantzig: Obviously, some modifications were made; for example, the bus would stop at my house instead of on the corner of my block. But because of how my parents raised me, I always believed I could do anything. My mobility has always been limited, but at that time, I could walk some distance without crutches and canes; one cane was usually enough when I was young.

I was also fortunate to have a lot of amazing friends. I did a lot of “normal” stuff in high school: I was involved in everything, from being the team mascot for four school sports to working on the stage crew for our high school plays. I remember a physical education teacher in elementary school who really carved out space for me; he refused to let me sit in the bleachers. Anything I could do, he would make sure I did it. I couldn’t play dodgeball in the typical way, so I sat on the dividing line, challenging players to get me out! I wound up catching most of the balls thrown at me. That was impactful and contributed to my outlook and the possibilities I saw for myself growing up. I didn’t let CP stop me; I simply did not understand that I wasn’t supposed to do those things.

Q: What inspired you to pursue a career in psychology and education? How did your experiences shape your approach to working with children with disabilities?

Dr. Dantzig: Developmental psychology, and Jean Piaget in particular, have always been of interest to me. I also fell in love with photography, so it was a tough call. The job that would pay the bills won the battle. I applied to a dozen Ph.D. programs for developmental psychology and got accepted to exactly none of them. I also applied to one program for school psychology. It happened to be at the Rutgers University Graduate School of Applied and Professional Psychology, which was, and arguably still is, the best program in the country.

I became an expert on developmentally based cognitive assessments and applying the results to educational programming. I was the lead author of A Guide to the Theory, Administration and Interpretation of the Southern California Ordinal Scales of Development: Cognition (now out of print).

I suppose the empathy I have as someone who has a disability – who is different – and my unique experience with having a strong support system in my family and friends inspired me to work with kids and be an educator. I appreciate an open and honest dialogue about what’s happening — how to prepare these kids for a life that is just as important and valid as anyone else’s. I have worked with people with severe IDD, and the disability does not have to define the person. Often, we have pity. Many of us have the wrong feeling that people with disabilities are less than a whole person.

Fast forward to September 11, 2001, I recall wandering around the school hallways numb after learning the news about the terrorist attacks. It was just so overwhelming, especially as someone from New York. But I had this student who was nonverbal, and she had no concept of what happened. She was just happy to see me! She radiated joy no matter what was happening around her. And that’s when I realized how wonderful it was to have her in this world — to exude joy and illuminate the darkness we carry. She lifts us up with her relentless smile when we are burdened by reality and how complex life can be. How is that a bad thing? It’s a beautiful existence!

So, I like to take life from that point of view. I never stopped trying to help or teach my students, but I accepted them and loved who they were. If you let them, they will teach you so much more.

Q: What are the biggest challenges facing students with disabilities today?

Dr. Dantzig: I use the square peg in a round hole analogy. In other words, we see people (with and without disabilities) as we think they “should” be rather than as the beautiful people they are in whatever shape and size they are. Every person is different and helping them along their unique paths is what we should be doing. Instead, we try to conform them to what we think is “normal.”

Q: What motivated you to transition from school psychology to your role at UCP Association of Hawai’i? What initiatives are you most excited about?

Dr. Dantzig: I served on the UCP Association of Hawai’i’s board of directors for ten years, consistently advocating for better support for adults with CP. I resigned from the board due to a major surgery; I wasn’t sure how my mobility would be affected. All went well, and now I’m back!

While UCP does incredible work with children, there is increasing but still little focus on CP’s impact or progression in adulthood. The common belief that CP is nonprogressive is partly true: the lesion in the brain does not progress; however, research shows that physical challenges increase with age. My own experience, transitioning from crutches to a power wheelchair, highlights the dramatic decline in motor function and the rising pain levels many face.

When Executive Director John Nishida invited me to join the staff, we discussed launching a research project to identify adults with CP in Hawai’i, assess their physical and mental health, and develop resources tailored to their needs. Alongside Dr. Joy Mahiko, associate professor at the University of Hawai’i-West O’ahu, and Brian Kajiyama, M.Ed., instructor at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, I am leading this effort to collect crucial data to understand the needs and create new support systems.

CP doesn’t necessarily shorten lifespan, yet aging with it presents unique challenges — decreasing mobility, increased spasticity and a higher risk of depression. Fear of falling and lack of physical activity further impact overall health and well-being. Meanwhile, the societal cost of CP care averages $1M per person over a lifetime. Understanding these realities allows us to advocate for better programs, services and proactive healthcare.

Sixty years ago, I was a patient at a UCP clinic. Now, I’m working to expand the organization’s reach in Hawai’i and maybe even across the entire UCP network. I thought I had retired from disability advocacy, but the universe has other plans!

Q: How has public perception of cerebral palsy changed over the years, and what still needs to be improved?

Dr. Dantzig: Great question! In many ways, it has changed dramatically; in other ways, it has not changed at all. A lot of people simply do not see you if you are different, especially if you move in different ways or if you are in a wheelchair. You become invisible — a blind spot people don’t want to look at.

One time, maybe 20 years ago, a friend and I went to I’olani Palace in Honolulu. We got a wheelchair to make it easier to see the palace. I love Hawai’ian history, and I was researching a personal project. So, I asked a palace employee where to find specific information, and the person looked over me and responded to my friend. My friend responded, “Why are you answering to me? He asked the question!”

Another example: I showed someone my photographs and the response was, “Wow, you took this photo?” I replied with some snark, “No, I stole it and put my name on it.”

Unfortunately, there is still a belief that people with physical disabilities are invalids. Break that word up and reread it: in-valid!

People stare. That is just a fact. I am human, and I look, too. However, I look at it from a different perspective: I am fascinated by how people adapt when their bodies don’t work as expected.

Q: Your autobiography shares some incredible stories. What’s one moment that encapsulates your philosophy on life?

Dr. Dantzig: When I was very young, my mom, with tears in her eyes, would tell me, “Get up, your bus is here.” It became a mantra: Life is hard for all of us, and you’ve got two choices: get on the bus or let it pass you by. I am not saying that any of this is easy. Living with CP is undoubtedly frustrating, painful and difficult; some things are much harder and take a lot longer to do. But it can also be a gateway to extraordinary growth if you embrace the opportunities our challenges provide — our unique perspective. That is the choice we all face. You rise to the challenge and push forward or risk being left behind.

Q: What advice would you give to young people with disabilities trying to find their path?

Dr. Dantzig: Take action. Serendipity is simply a passing moment if you do not act on it. I have done some amazing things in my full life because I acted on the opportunity. I have also spent many hours on projects that did not go anywhere, but those aren’t failures. You will never know unless you take action.

Two more: Don’t assume that you can’t do something and ask for and accept help when you need it. It never occurred to me that I couldn’t ski, bowl, SCUBA dive, play on a softball team (my batting average for six years was .000!), golf, surf, write books, become a renowned photographer (for a while!) or travel to places like the Philippines, Singapore and Australia. I just did them — with more and more assistance as I grew older, but I still did them. I look back at my life as I enter my golden years, and it has been an amazing ride. One of my favorite lines is from Jimmy Buffett’s song, “I Went to Paris”: “… Some of it’s magic, some of it’s tragic, but I had a good life all the way.”

Q: UCP’s tagline is “Life without limits for people with disabilities.” What does that mean to you?

Dr. Dantzig: Everybody has limitations. There is no such thing as a person without a limitation. So, it’s not so much about life without limits, but it’s really about living life to the fullest despite your limitations. How you cope and navigate those challenges is the key to that message. And for UCP, that means being a resource to help people embrace all that is possible, never focusing on what is not.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of Dr. Stephen Dantzig and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of United Cerebral Palsy or its affiliates.

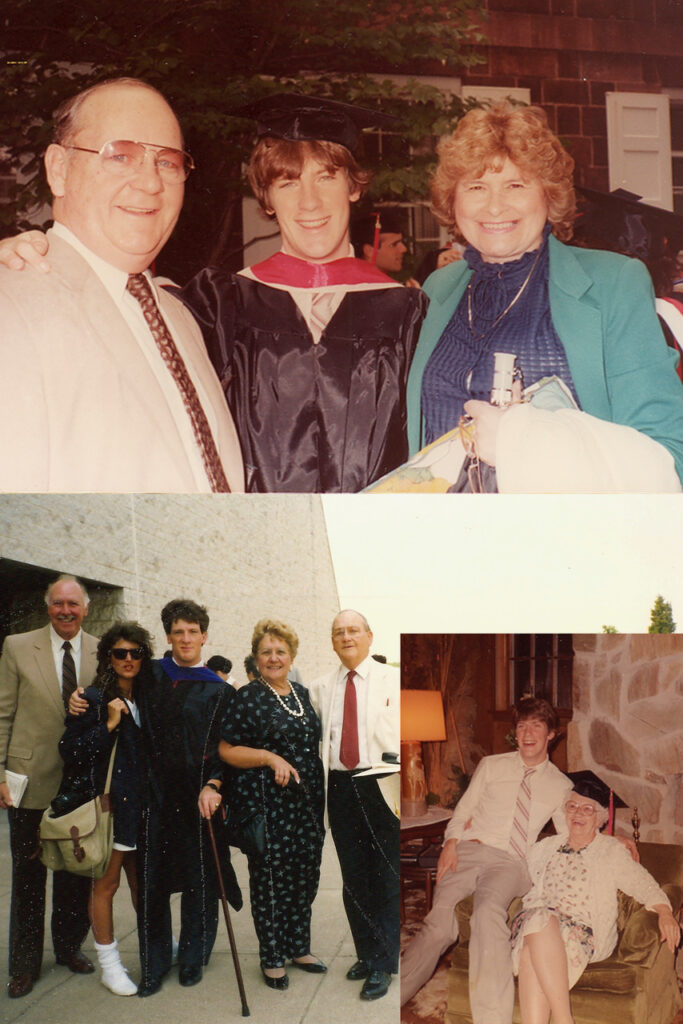

Photos are courtesy of Stephen Dantzig and Robert Hernandez.